Over the past few months, the additional help of several summer interns has meant that TreeHouse has been humming with activity as projects that have been backed up for ages get wrapped up one after another. For me, the biggest step came a couple of weeks ago, when we completed work on our new deer pen.

The deer pen has been in the planning stages since last winter. It was originally intended to have been completed in time for last year’s fawns, but a number of factors ultimately made that goal untenable. To me it was beginning to feel like the enclosure would never be started. Even after the materials had been ordered and delivered, it seemed like the weather would never cooperate. So, the first time we had an open afternoon, a few of the interns decided we just needed to start it.

Looking at the enclosure in person, it’s pretty easy to imagine guard towers at the corners and crossbows peeking out between the posts.

With the help of a lot of hard work by interns and volunteers, the pen went up remarkably quickly. The enclosure is more than 1500 square feet, and it includes a swinging gate that allows us to separate specific individuals if necessary. It also, with a bit of imagination, looks exactly like a medieval fortress.

Apparently, TreeHouse interns tend to have a certain number of shared interests. Maybe that should be obvious—clearly, something drew all of us to want to intern at TreeHouse. So maybe I shouldn’t have been so surprised when I mentioned the Redwall books and found that both of the interns I was talking to had also read them as kids.

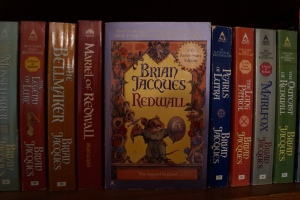

A portion of the combined collection of my brother’s and my Redwall books. Apparently there are a total of 22 books in the series.

For those of you unfamiliar with Redwall, it is the name of an abbey populated and defended by an assortment of woodland creatures in a series of novels by Brian Jacques. I loved the Redwall books when I was younger, but I haven’t met many people who read them. Evidently they’re very popular among TreeHouse interns though. So it was sort of obvious to all of us, once the name had been brought up, that our new deer pen had to be called Redwall. At the moment it basically has a moat along the east wall where a new water line was put in a few months ago, it is currently housing about a dozen fawns, and as more of our new rehab enclosures are completed in the coming months, it will be increasingly surrounded by assorted woodland creatures. I’m not sure if the name is actually official, but to those of us who built it, it will always be Redwall.

The fawns themselves, meanwhile, seem very pleased with their new housing. Before the enclosure was completed, they had been staying in an indoor exercise room. They were quite young at that point, so the situation wasn’t bad, but the outdoor enclosure gives the growing fawns a much healthier and richer environment. The fawns, predominantly car-strike orphans, will live and grow in Redwall until this fall, when they are old enough to set out on their own. In the meantime, I suppose we’d just better keep a lookout for an invading horde of weasels wielding battleaxes.